Why Architecture Should Always Carry Meaning

A few months ago, my friend Taina Guedes, Brazilian food-artist based in Berlin, came to us – Sven Hoehne and myself – asking for a favour: can we build a mobile-kitchen-instrument? Strange question…we know we can build a kitchen. We know we can make it move. We suppose it can make sounds too? So, I answered as an architect would:

Yes, of course! We can make a mobile-kitchen-instrument. What is the budget? What is the timeframe? What equipment do you have? What is the architect’s fee?

She replied: Fantastic! (and...the budget is non-existent but I can buy a couple of things for you; it has to be done over 4 weeks time with 10 year old kids at the school; equipment? Well…I have some tools; we are all working for free…and if the project is successful, we'll maybe get paid the second year!)

I said: Cool! (So basically, we have to build something with nothing but time and motivation? What a challenge! Is anybody else as motivated by challenge as architects?)

The mobile-kitchen-instrument was in fact a small part of a year-long project by Taina Guedes and Lynn Peemoeller at Papageno School in Berlin-Mitte, aiming to sensitize children to the problematic of quality of food, sustainability and waste through an artistic and musical initiative. The kids would grow their own vegetables and plant pumpkins. The pumpkins would then be transformed either into a delicious dish to share prepared on site with the kids or into a traditional musical instrument with help of specialists. The goal is to develop the kid’s interests in different fields, expanding their knowledge through curiosity and making. The mobile-kitchen becomes an event as well as a mediator, educating broader public through the kids about the politics behind food production and consumption.

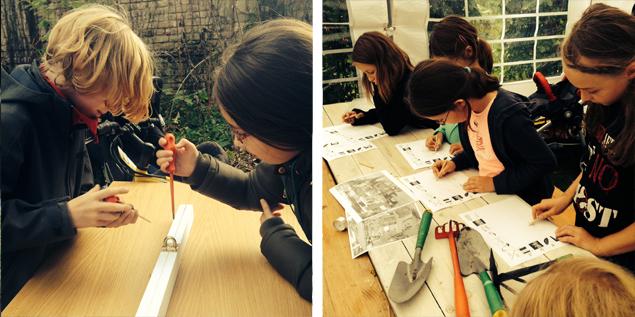

Of course, such project without a budget can't in the end look like a mini-Guggenheim-Bilbao. To make it possible, the expression of the kitchen has been reduced to the bare minimum: a horizontal surface to accommodate different uses: washing, cutting, cooking. We used objects and materials at hand: two bikes, a door and some wooden sticks. We thought about how to make the connections: as this needed to be realized on site with the kids, it had to be safe. No cutting, no welding. Just screwing. Like a Berliner IKEA-kit, made with somebody else's trash. Keen to transform the simple act of making into inspiration about architecture, we split the course into three parts:

Drawing: imagining and thinking

Measuring and modelling: testing the hypothesis

Building: making things happen

After the success of drawing and the failure of modelling (probably due to the impossibility of transforming an architect into a teacher and the difficulty of remembering what it was to be a 10 year old!) the making was extremely popular amongst the kids. By fighting over the few screwdrivers, they showed dedication to the action.

But what struck my attention was rather what was happening around us. We were building the mobile-kitchen at the school garden surrounded by beautiful trees, where pumpkins were growing and where other kids of all ages came to water the vegetables. A gate to the playground opens up directly onto the garden. At the playground I was almost punched by a couple of kids riding wildly on scooters while further along, a hidden trampoline sent small bodies magically up in the air, again and again. At the same moment, a kid with stilts fell on the ground, stood up and tried again. Some of you may be already familiar with such play environments where nature and possible danger is part of the programme, but I personally was astonished by this spectacle.

But what struck my attention was rather what was happening around us. We were building the mobile-kitchen at the school garden surrounded by beautiful trees, where pumpkins were growing and where other kids of all ages came to water the vegetables. A gate to the playground opens up directly onto the garden. At the playground I was almost punched by a couple of kids riding wildly on scooters while further along, a hidden trampoline sent small bodies magically up in the air, again and again. At the same moment, a kid with stilts fell on the ground, stood up and tried again. Some of you may be already familiar with such play environments where nature and possible danger is part of the programme, but I personally was astonished by this spectacle.

In 2008, I was the architect responsible for the first passive public building – the Lucie Aubrac School in southern France for the firm Laurens & Loustau in Toulouse. The school was to be the central part of an ‘écoquartier’ (eco-neighborhood). Used and then re-used from both right and left political parties successively in power in Toulouse, Lucie Aubrac School was carrying the ambitions and the desires of the future.

But from those initial ambitions to completion, a series of discussions and negotiations took part in the meeting room, confronting us – the architects and landscape architects – with a compound of people in charge from the City – future education, future security, future maintenance, future energy and future elections. Here you can find a glimpse of the arguments heard through those long hours, in response to our design proposal.

The Architects: Here, we propose a garden where kids could grow their own vegetables and through this simple action discover, learn and play.

The City: That's not possible. The kids would go back home with dirty clothes as a result of contact with earth. The parents will complain. No earth. No garden.

The Architects: Here, we plan to have a couple of tall trees that could regulate light and temperature. And the kids could watch them changing through the seasons. They could be fruit trees so that the kids enjoy picking the fruits when it’s the perfect moment.

The City: That's not possible. If there are trees, they must bear no fruits. No fruits at all. Understand. If they bear fruits, then it will be more work for the person in charge of cleaning. And they won't agree with this extra job allocation. Also, the fruits that are falling from a tree are often too ripe. It will make a big mess. Please give us a selection of fruitless trees.

So? How did the final project turn out? Despite the austerity of the final design, Lucie Aubrac School turned architecturally to be a good project and I am still very proud of it. Just recently, it has been elected "Lauréat des prix de l'architecture Midi-Pyrénées". But how could it have been better? Is that really up to us, architects? And if so, what can we do to try and improve it? And what do we learn from both projects?

So? How did the final project turn out? Despite the austerity of the final design, Lucie Aubrac School turned architecturally to be a good project and I am still very proud of it. Just recently, it has been elected "Lauréat des prix de l'architecture Midi-Pyrénées". But how could it have been better? Is that really up to us, architects? And if so, what can we do to try and improve it? And what do we learn from both projects?

Every architectural project, from the really small scale to the really large is about learning the politics of either controlling it – active behaviour – or letting it be – passive behaviour. Saying that every architectural decision is co-dependant on a political one seems obvious but worth to be underlined. If we consider every architectural project as the possibility to engage in a public debate where the people are its focus, architecture becomes politics. Hence architecture matters. Any architecture, or moreover any ‘action of architecting’ is therefore political.

Today, comparing those two schools, I have the intuition that it is simply better to study in one of them. Unfortunately, I'm afraid it is the one I haven't drawn.

Joanne Pouzenc is an architect, architecture critic and tutor living and working in Berlin. She is the co-founder of Collagelab, a platform for prospective thinking and research in architecture and urbanism.